Jules Verne and the worlds we inhabit [Worldbuilding Series, Part 2]

Guest Post by Stefy Bolaños, writer of "The Learning Dispatch" on Substack

Jules Verne and the worlds we inhabit [Worldbuilding Series Part 2]

This is a guest post by my dear friend and talented writer, Stefy Bolaños. Read more of Stefy’s work on her Substack, The Learning Dispatch, a newsletter dedicated to exploring innovative formats and creative methods in the world of learning.

Jules Verne knew how to build a world. His stories constructed entire ecosystems, each with its own rules, technologies, and uncharted frontiers.

Imagine him now, not as the 19th-century writer with ink-stained fingers, but as a game designer, a learning architect, or a creator of immersive experiences. Would he be coding an open-world adventure game? Designing interactive learning maps? Sketching out a new kind of gathering where people step in to self-contained universes?

Take Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. This novel was a carefully designed ecosystem where the Nautilus functioned as its own microcosm, complete with an internal economy, technological marvels, and philosophical rules dictated by Captain Nemo. Verne created a self-sustaining world beneath the waves, filled with rules that felt natural even in their futuristic setting.

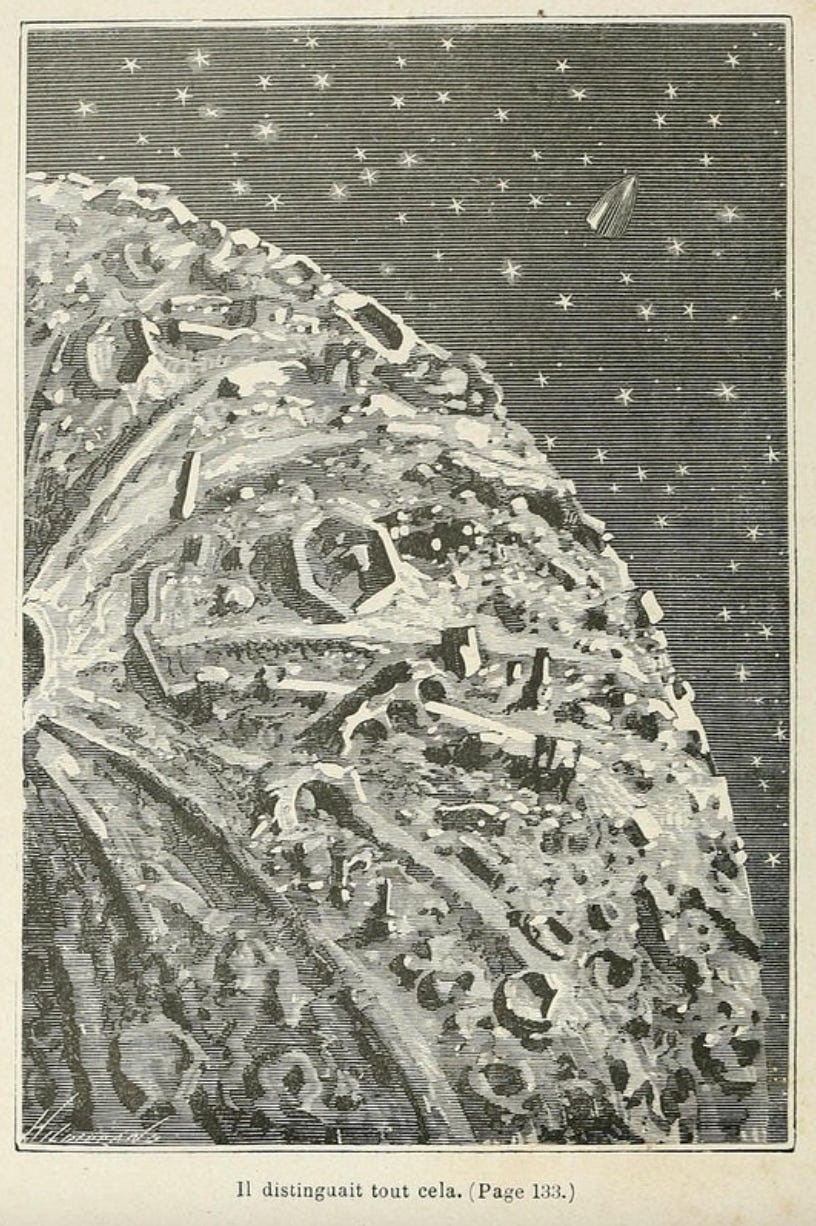

In Journey to the Center of the Earth, he crafted another world-within-a-world. The underground realm was filled with prehistoric life and geological formations that followed a strange but believable logic. The deeper the explorers went, the more they discovered about how this secret world functioned.

Even in From the Earth to the Moon, his vision of space travel was strikingly detailed. He accounted for physics, engineering, and even the financial and political machinations behind a moon launch, long before the Apollo missions. Instead of simply sending his characters to the Moon; he built a system where space travel felt possible.

Jules Verne built environments that lived beyond the page. He built worlds that functioned with an internal logic so precise that, even today, they feel eerily predictive. He understood that true worldbuilding is about creating a space where choices unfold organically, where readers (or players, learners, or travelers….) can shape their own narratives.

The World of 80 Days

One of Verne’s most famous works is Around the World in 80 Days. The novel follows the wealthy and enigmatic Phileas Fogg, who wagers that he can circumnavigate the globe in eighty days. With his loyal valet, Passepartout, Fogg embarks on an adventure that takes him across Europe, through India, Japan, America, and back to England. Along the way, he faces challenges: trains breaking down, political turmoil, and even an obsessive detective convinced that Fogg is a bank robber on the run. The novel captures the tension between the old world, where travel was slow and uncertain, and the new industrialized world, where speed and efficiency were becoming essential.

Decades later, the game 80 Days took Verne’s premise and turned it into an interactive experience where the story is shaped by the player’s actions.

What I loved about 80 Days is that it doesn’t force a narrative. It builds a world. Instead of a rigid sequence of events, it offers a playground of possibilities. Every train boarded, every conversation had, every object purchased changes the trajectory of the journey. The game doesn’t dictate a single story; it invites exploration within a structured yet flexible environment.

And here’s where worldbuilding gets really interesting: the more open-ended a world feels, the more rigorously designed it has to be. The rules must be invisible but solid. Choices must matter, even if their consequences aren’t immediately apparent. Players need to feel the weight of their decisions, even in a system without an overt morality scale.

I’ve played it a couple of times now, and I’m surprised by what needed to happen in the story for me to recognize the 'invisible' rules at play, like the way my own personality might dictate a possible outcome. Every time I play, I notice new patterns; subtle nudges guiding me toward different possibilities…

The worlds we walk through

We inhabit many worlds. Some are obvious: our homes, our cities, our favorite coffee shops where the barista knows our order before we say it. Others are more fleeting but no less real. Walking the Camino de Santiago, for instance, felt like stepping into a universe with its own language (Buen Camino!), its own culture (pilgrims, hostels, the ritual of tending to blisters), and its own mythology (legends passed down on dusty trails). It was a world that existed within but separate from the one left behind, shaped by invisible rules and shared rituals.

Teaching a class is another form of worldbuilding. A syllabus is a map. A classroom is a designed space. A learning culture is its own ecosystem of rules and rituals, where what is left unsaid is just as important as what is explicitly taught. As educators, facilitators, or experience designers, we are constructing a space where learning, discovery, and agency can unfold.

The Mechanics of good worldbuilding

Great worldbuilding, whether in fiction, games, education, or travel, relies on the same fundamental principles:

Constraints create freedom. Just as Verne gave the Nautilus limits (its fuel, its secrecy), a well-designed learning experience benefits from structure. Too many options without logic lead to chaos; well-crafted constraints make exploration meaningful.

Choices must matter. A great world responds to its inhabitants. Whether it’s a player navigating a game, a student engaging with a lesson, or a traveler choosing their next path, the best worlds make decisions feel consequential.

Rules should be invisible but firm. Even in the most imaginative of settings, internal consistency is crucial. A world, whether built for play or learning, needs logic that feels natural, even when unspoken.

Surprise keeps engagement alive. The best worlds allow for unpredictability: hidden corners, unexpected discoveries, the ability to break the expected pattern. Learning, like adventure, should leave room for the unknown.

The Worlds We Choose to Build

Whether we’re crafting a game, hosting a gathering, designing a learning journey, or walking an ancient trail, we are always engaging in worldbuilding. The question is: What kind of worlds do we want to create?

Do we want ones that exclude or ones that invite? Ones that dictate or ones that explore? Do we design rigid paths or dynamic ecosystems where people can chart their own course?

At their best, the worlds we build should be playful, open-ended, and flexible. They should allow for uncertainty, for surprise, for stories that no one could have predicted. And most of all, they should remind us that every step (on a trail, on a map, in a game, or in a classroom) is a choice we get to make.

Just like Jules Verne, we aren’t just telling stories. We’re building worlds worth stepping into.

Thank you Stefy for the fascinating insights on Worldbuilding! Check out Stefy’s Substack here, and come back soon for my installment on Worldbuilding for this 2-part series.

Read More Newsletters on Storytelling:

I Paid Someone to drop me in the middle of the mountains for eight days with no phone or map

The Hidden Meaning of Lost Objects

Dinner with Soviet Defectors and FBI Agents

Read the Coop-to-Museum Series:

From Memoir to Museum: How I Found Myself in a Chicken Coop

Catch up on some of my favorite and most-read newsletters:

My Husband tried to impress me by inventing Ethernet 50 years ago

The World Championships of Cheese